November 11, 2025

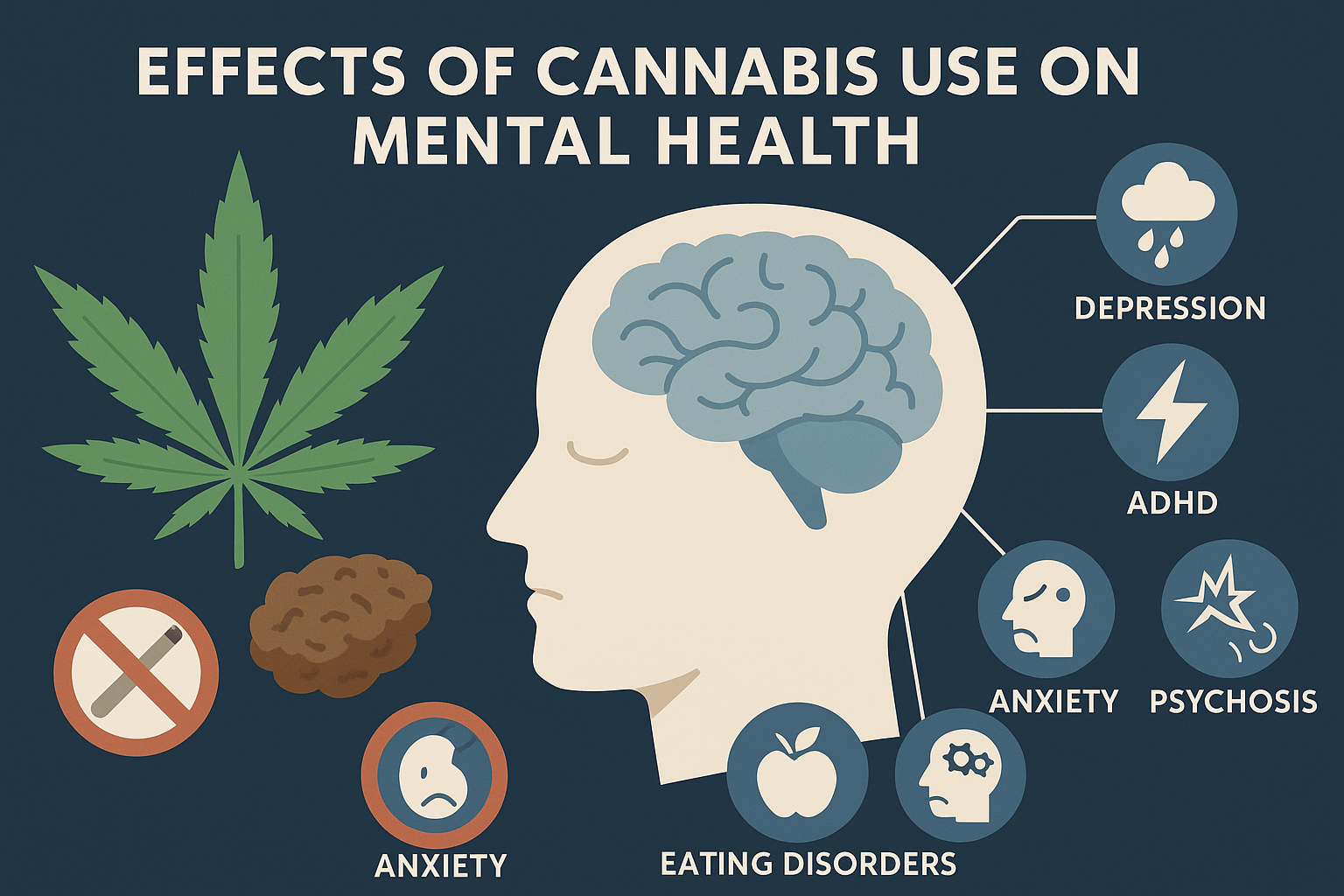

Effects of cannabis use on mental health: explore links with depression, anxiety, ADHD, psychosis & how Integrative Psych can help.

The interplay between the psychoactive substance Cannabis and diverse facets of mental health has become increasingly complex amidst changing patterns of use, potency, age of initiation and comorbid psychiatric conditions. This article examines the effects of cannabis use on mental health, exploring how cannabis may interact with or influence conditions such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, OCD, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder (BPD), psychosis and eating disorders. Our goal is to aid clinicians, researchers and informed consumers in understanding current evidence, caveats, and clinical implications.

Use of cannabis, particularly daily or near-daily and/or high-potency products, has been associated with increased risk for mental health disorders. For example, government health authorities in Canada note that daily or near-daily cannabis use over time can increase chances of developing anxiety and depression, impair brain function (e.g., dopamine system disruption) and elevate risk of psychosis and schizophrenia in vulnerable individuals. Systematic reviews also suggest that heavy cannabis use is linked to worsened psychiatric symptoms and increased incidence of psychotic disorders.

That said, the direction of causality (whether cannabis precipitates the disorder, exacerbates it, or is used as self-medication) remains subject to ongoing research and debate.

Multiple longitudinal studies indicate that frequent cannabis use (e.g., weekly or more often) is associated with an elevated risk of depressive symptoms over time. For instance, one prospective review found that young adults who used cannabis weekly were more likely to report heightened depressive symptoms over a 5-year period, especially if they began use early (before age 15). Moreover, heavy use may be linked to suicidal ideation and attempts.

Mechanisms may include altered endocannabinoid and monoaminergic signalling, dysregulation of reward circuits, or motivational deficits (sometimes called “amotivational syndrome”).

While some users report transient relief of anxiety symptoms with cannabis, evidence suggests that chronic frequent use may worsen anxiety or contribute to new anxiety disorders. For example, daily use has been associated with poor emotion regulation, elevated anxiety over time, and increased dependency risk. Given the mixed findings, clinicians should remain cautious about using cannabis as an anxiolytic.

From a therapeutic perspective, patients presenting with mood disorders who also report cannabis use should be assessed for frequency, age of initiation, potency of product, co-use of other substances and family history of psychiatric illness. Reduction or cessation of frequent cannabis use is often a worthwhile component of mood disorders management.

Cannabis use intersects with ADHD in complex ways. Some individuals with ADHD report using cannabis in an attempt to self-medicate symptoms (e.g., restlessness, impulsivity, sleep problems). A 2024 study found significant associations between cannabis use frequency/quantity and ADHD symptom load, even after adjustment for confounders.

However, the evidence does not support cannabis as an effective treatment for ADHD; rather, regular use may exacerbate executive dysfunction, impair academic/work performance and increase risk of cannabis use disorder (CUD).

Therefore, in clinical settings, ADHD patients should be screened for cannabis use patterns, and non-substance based evidence-based treatments (medication, behavioural therapy) remain first-line.

Although less studied than mood or psychotic disorders, there is emerging interest in cannabis use in OCD presentations. Some users turn to cannabis to manage anxiety or intrusive thoughts, but robust evidence of benefit is lacking. The risk is that cannabis may dampen insight or contribute to avoidance behaviours, worsening the OCD cycle.

Given paucity of data, the prudent clinical stance is to regard cannabis use in OCD as a potential complicating factor, particularly when it co-exists with other substance use or mood symptoms.

In the context of personality disorders such as BPD, patterns of substance use— including cannabis— tend to reflect underlying impulsivity, emotion dysregulation and self-medication. Genetic work suggests that individuals with BPD have elevated rates of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder.

Clinicians treating BPD should assess for cannabis use, as it may worsen affective instability, increase risk of self-harm, interfere with DBT/skills practice and impede psychotherapy progress.

One of the strongest associations in the literature is between cannabis (especially high-potency THC, early onset use, heavy frequency) and psychotic disorders. A meta-analysis found that use of higher potency cannabis was associated with increased risk of psychosis and cannabis use disorder.

For example, heavy daily use in adolescence has been linked to earlier onset of schizophrenia. While causality remains unresolved, there is robust evidence of a dose-response relationship and that THC content matters significantly.

Clinical implications: In patients with a first‐episode psychosis, any cannabis use (especially high-THC products) should be considered a modifiable risk factor. Early screening and intervention for cannabis use may alter trajectories.

Cannabis interacts with appetite, reward systems and body weight; its role in eating disorders is nuanced. Genetic studies show that cannabis use and cannabis use disorder may have comorbidity with anorexia nervosa and other disordered-eating presentations. Some individuals with eating disorders might use cannabis to stimulate appetite or calm anxiety, yet heavy frequent use may undermine cognitive control, amplify body-image distortion and impede recovery. Clinicians working with eating-disorder populations should inquire about cannabis use as part of holistic risk stratification.

Beyond discrete psychiatric diagnoses, heavy and early cannabis use (especially before age circa 25, when the brain is still maturing) can impact attention, working memory, executive functions and motivation. A recent study found that heavy cannabis users had reduced brain activity during working memory tasks compared with non‐users. In adolescent users, such changes may persist or interact with risk for later mental health problems.

The strength of associations between cannabis and mental health outcomes depends heavily on three modulating factors:

Several plausible mechanisms may explain how cannabis use influences mental health:

For clinicians, mental-health professionals, and service providers (including those in integrative care):

While substantial epidemiological evidence exists, causality remains uncertain for many outcomes (especially mood/anxiety disorders). Key gaps include:

At Integrative Psych, our mission is to deliver forward-thinking, evidence-informed mental-health care across the lifespan. With clinical teams in Chelsea, NYC and Miami, we are positioned to integrate advanced assessment protocols (including substance-use screening) with psychotherapeutic modalities, medication management, neuro-cognitive monitoring and digital biomarker technologies. If you or a loved one are exploring how cannabis use may be affecting mood, attention, personality, behavior or cognition — our experts are here to help. Learn more about our practice, our multidisciplinary team and how we can design a personalized care pathway tailored to you.

We're now accepting new patients